Surveillance Biopsy: Boon or Bust?

Michael Seifert2, Miriam Bernard1, Roslyn Mannon1.

1Medicine, Nephrology, UAB, Birmingham, AL, United States; 2Nephrology, Childrens of Alabama, Birmingham, AL, United States

UAB Transplant Nephrology.

Introduction: While not particularly sensitive, serum creatinine remains the primary non-invasive method of monitoring functional allograft health. Allograft biopsies are more sensitive in detecting injury, and some transplant centers use early surveillance biopsies to assess the adequacy of immunosuppression when the creatinine is stable. However, controversy exists as to whether treatment of surveillance findings has a positive impact on kidney transplant outcomes. We initiated a surveillance biopsy program at our center in May 2015 to improve clinical outcomes. This study is an interim analysis of our surveillance program to determine outcomes of subclinical inflammation.

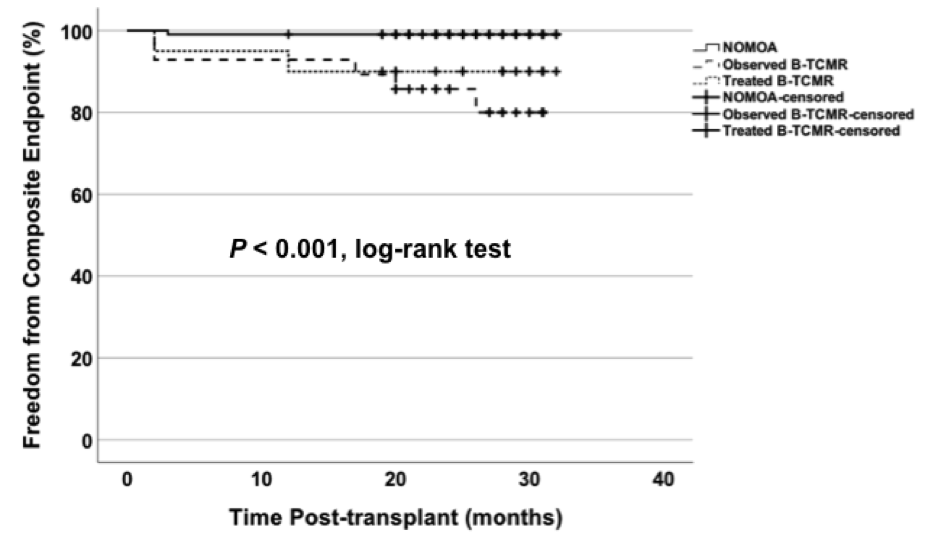

Materials and Methods: We screened a clinical database of all kidney transplant biopsies performed at our center between May 2015 and December 2016. Surveillance biopsies were defined as those performed at 6 months post-transplant in the setting of normal/stable allograft function. We collected clinical and demographic data from the medical record of each participant, including up to 32 months of follow-up. The primary exposure was subclinical inflammation (SCI), which we defined as subclinical acute rejection (SC-TCMR) or borderline acute rejection (B-TCMR) based on Banff 2013 criteria. Secondary exposures included routine clinical/demographic variables and treatment of surveillance findings (clinician’s discretion). The primary outcome was a composite endpoint of acute rejection after surveillance and death-censored allograft loss. Our primary hypothesis was that subclinical B-TCMR, which is often not actively treated, will lead to worse outcomes compared to those with no major surveillance abnormalities (NOMOA).

Results and Discussion: We reviewed 601 kidney biopsies performed during the study period, 166 (28%) of which were 6-month surveillance biopsies. Notably, our cohort was enriched for higher immunological risk recipients (55% black and 61% deceased donors). Mean clinical follow-up was 22 months. Overall patient, graft, and rejection-free survival (after surveillance) were excellent at 99%, 96%, and 95%, respectively. The primary composite endpoint was reached in 10/166 (6%) of subjects. SCI was detected in 57/166 (34%) surveillance biopsies, of which 48 (29%) were B-TCMR and 9 (5%) were SC-TCMR. All SC-TCMR and 42% of B-TCMR were treated with increased immunosuppression at the clinician’s discretion. This included increased maintenance therapy as well as corticosteroid pulse therapy. The incidence of the composite endpoint was 15% with B-TCMR on surveillance versus 1% with NOMOA (P<0.001), and was significantly impacted by treatment at only 10% in treated B-TCMR compared to 18% in those expectantly managed (P=0.005, see Figure).

Conclusions: SCI was detected at 6 months in > 30% of kidney recipients, most of whom had B-TCMR. Although sample size was limited in this interim analysis, there may be long-term benefits of treating subclinical B-TCMR. Defining those that may benefit from treatment is a critical issue in kidney transplant management.

UAB Kidney Undergraduate Research Program.