Increased Serum Sodium Values in a Brain-Dead Donor do not Influence the Long-Term Kidney Function

Mamoru Kusaka1, Akihoro Kawai1, Shinji Iio2, Naohiko Fukami1, Hitomi Sasaki1, Takashi Kenmochi3, Ryoichi Shiroki1, Kiyotaka Hoshinaga1.

1Urology, Fujita-Health University, Toyoake/Aichi, Japan; 2Japan Organ Transplant Network, Tokyo, Japan; 3Transplant Surgery, Fujita-Health University, Toyoake/Aichi, Japan

Background: Kidney transplantation is often performed with brain-dead donors with associated endocrine disorders. Diabetes insipidus, the most common complication, results in hypernatremia, hypovolemia, and increased plasma osmolality. Hypernatremia in donors is one of the strongest risk factors for the loss of a transplanted liver or heart because of cell swelling and a resultant increased severity of reperfusion-mediated injury. However, the influence of donor hypernatremia on the early and late kidney graft function has not yet been conclusively established. In this study, the post-transplant outcomes of renal allografts recovered from brain-dead donors with hypernatremia were compared to those of donors without hypernatremia.

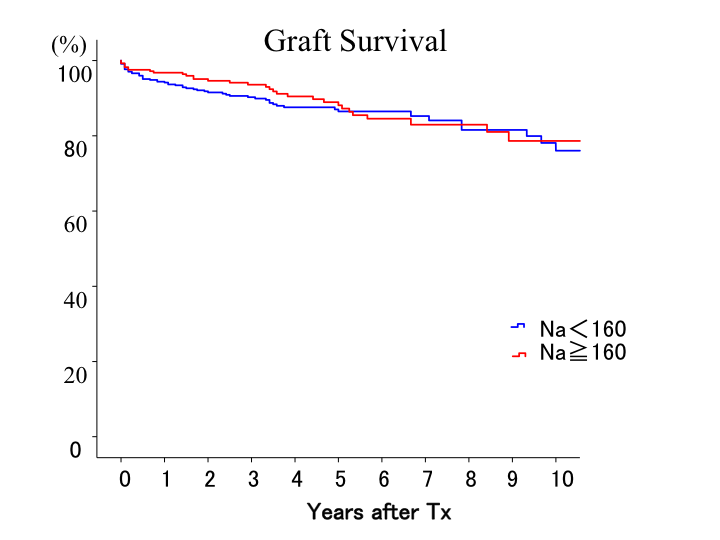

Methods: We analyzed data for 765 kidney recipients from 386 brain-dead donors from 1999-2016 using the Japan Organ Transplant Network (JOT) database. Donors were divided into 2 groups based on sodium concentrations of <150 or ≥150 mmol/L and <160 or ≥160 mmol/L. The differences in the graft survival among the groups were examined with the Kaplan-Meier method and compared using a log-rank test.

Results: The mean donor age was 44.5±15.1 years, and the mean recipient age was 47.3±13.5 years. The median total ischemic time was 546 minutes (range 169-1365). The median final serum creatinine level measured in donors before procurement was 0.79 mg/dl (range 0.10-10.37). The cause of death of the donor was cerebrovascular disease in 51.1% and head trauma in 19.7%. We compared the long-term graft survivals among the sodium concentration groups. The 1-, 2- , 3- and 5-year graft survivals in the <150 mmol/L sodium group (233 grafts) were 96.6%, 96.1%, 93.3% and 90.8%, respectively. The 1-, 2-, 3- and 5-year graft survivals in the ≥150 mmol/L sodium group (532 grafts) were 98.1%, 97.2%, 96.6% and 96.6%, respectively. There were no significant differences between these 2 groups (p=0.098). The 1-, 2-, 3- and 5-year graft survivals in the <160 mmol/L sodium group (477 grafts) were 97.7%, 96.6%, 96.6% and 95.1%, respectively. The 1-, 2-, 3- and 5-year graft survivals in the ≥160 mmol/L sodium group (288 grafts) were 97.6%, 97.6%, 96.8% and 96.4%, respectively. There were no significant differences between these 2 groups (p=0.429).

Conclusion: An excellent graft function and long-term graft survival were observed after kidney transplantation from brain-dead donors in Japan. High serum sodium concentrations and increased plasma osmolality in brain-dead kidney donors may suggest an adverse effect on the graft function, probably due to the initiation of inflammation processes. However, our results showed that the serum sodium concentration had no marked influence on the long-term graft survival. Given the severe organ shortage, we should not discard kidney grafts simply because the donor’s serum sodium concentration is high.