Current Status of Organ Donation for Transplantation in Vietnam

Sinh N. Tran1,2, Thu T. N. Du1, Sam M. Thai1, Hien T. Nguyen1,3, Tuan V. Bui1, Edward A.Y. Lo-Cao4, Henry Pleass3,4, Richard Allen3,4, Paul Robertson3, Son T. Nguyen1, Khanh G. Pham5.

1Cho Ray Hospital, Ho Chi Minh City, Viet Nam; 2Ho Chi Minh University of Medicine and Pharmacology, Ho Chi Minh City, Viet Nam; 3Westmead Hospital, Sydney, Australia; 4The University of Sydney, Sydney, Australia; 5Vietnamese Society of Organ Transplantation, Hanoi, Viet Nam

Aim Review known organ transplant activity in Vietnam (VN) since 1992 and describe current challenges for deceased donation (DD).

Materials and Methods Detailed organ donation recipient registries do not exist in VN. The national registry relies on self-reporting from 17 kidney, 3 liver and 3 heart transplant centers. Complete data is available from Cho Ray Hospital (CRH) in HCMC. All VN and English articles and abstracts relating to DD were reviewed and government legislation referred to.

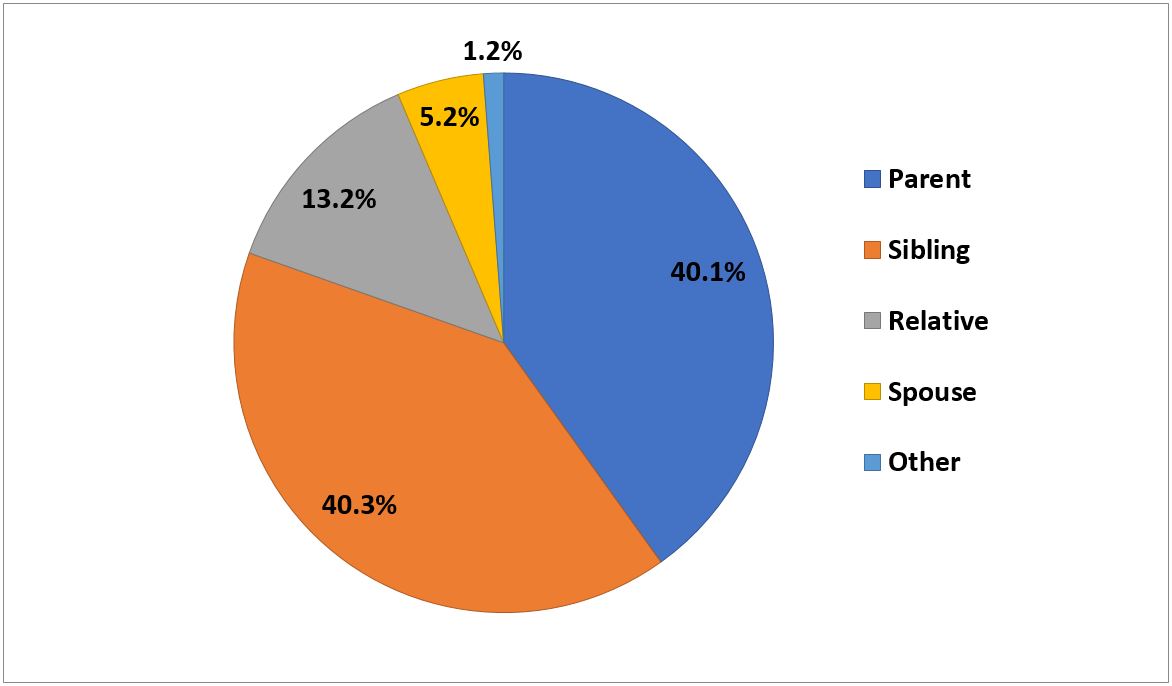

Results and Discussion 2,249 living donor (LD) transplants, 174 DBD transplants and 3 DCD transplants have been reported. No child has received an adult deceased donor organ. 3 of 17 kidney transplant centers presented data at 4th Congress of the Vietnamese Society of Transplantation (VSOT) in Oct 2017, reporting recent unrelated kidney donor activity of 6.3%, 71.4% and 85.7% respectively at CRH (Figure 1), and 2 Hanoi hospitals that rely on police or hospital committees to determine that unrelated donors were not rewarded.  Many barriers to DD exist in VN, despite DD legislation for brain dead patients ≥18 y.o. Yearly, >12,000 head injury deaths occur. Brain death diagnosis depends on EEG criteria and clinical diagnosis by both a neurologist and intensive care (ICU) specialist on 2 occasions and 12 hours apart. Government hospitals are under immense pressure caring for large numbers of patients with limited resources. This impedes ability to obtain family consent for DD. Requests are infrequent, cursory and not helped by absence of national or regional criteria for organ allocation and lack of published VN transplant results. An environment of trust between the ICU teams and transplant clinicians has not been created. DCD might better facilitate DD if practical VN guidelines existed. However waiting lists of recipients with known stored sera do not exist, limiting the ability to transplant DCD kidneys and livers expeditiously. Recently completed KC-10 study will assist the VN government to introduce national DCD protocols. DD remains an uncommon event, hence roles for hospital-based organ donation and recipient coordinators are not defined and limit multi-organ donation. Transplant team training from Europe, Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan has centered on excellence in surgical skills for elective LD procedures. Roles and career paths for transplant physicians and nurses are therefore less well developed for recipient preparation and long-term care.

Many barriers to DD exist in VN, despite DD legislation for brain dead patients ≥18 y.o. Yearly, >12,000 head injury deaths occur. Brain death diagnosis depends on EEG criteria and clinical diagnosis by both a neurologist and intensive care (ICU) specialist on 2 occasions and 12 hours apart. Government hospitals are under immense pressure caring for large numbers of patients with limited resources. This impedes ability to obtain family consent for DD. Requests are infrequent, cursory and not helped by absence of national or regional criteria for organ allocation and lack of published VN transplant results. An environment of trust between the ICU teams and transplant clinicians has not been created. DCD might better facilitate DD if practical VN guidelines existed. However waiting lists of recipients with known stored sera do not exist, limiting the ability to transplant DCD kidneys and livers expeditiously. Recently completed KC-10 study will assist the VN government to introduce national DCD protocols. DD remains an uncommon event, hence roles for hospital-based organ donation and recipient coordinators are not defined and limit multi-organ donation. Transplant team training from Europe, Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan has centered on excellence in surgical skills for elective LD procedures. Roles and career paths for transplant physicians and nurses are therefore less well developed for recipient preparation and long-term care.

Conclusion VN is a developing country with great potential to improve DD activity with cost effective resourcing and training of donation-dedicated ICU staff, cost recovery for DD organs, transparent organ allocation protocols and waiting-lists led by VSOT, and better hospital recipient team organization. In turn, growth of heart and liver transplantation and transplantation of children with adult organs will enhance community and donation sector appreciation of DD.