Should Donation after Cardiac Death Donor Organs be Used in the Pediatric Patient Population?

Christine Hwang1, Ali El Mokdad1, Swee Levea2, Malcolm MacConmara1.

1Surgery, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, TX, United States; 2Medicine, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, TX, United States

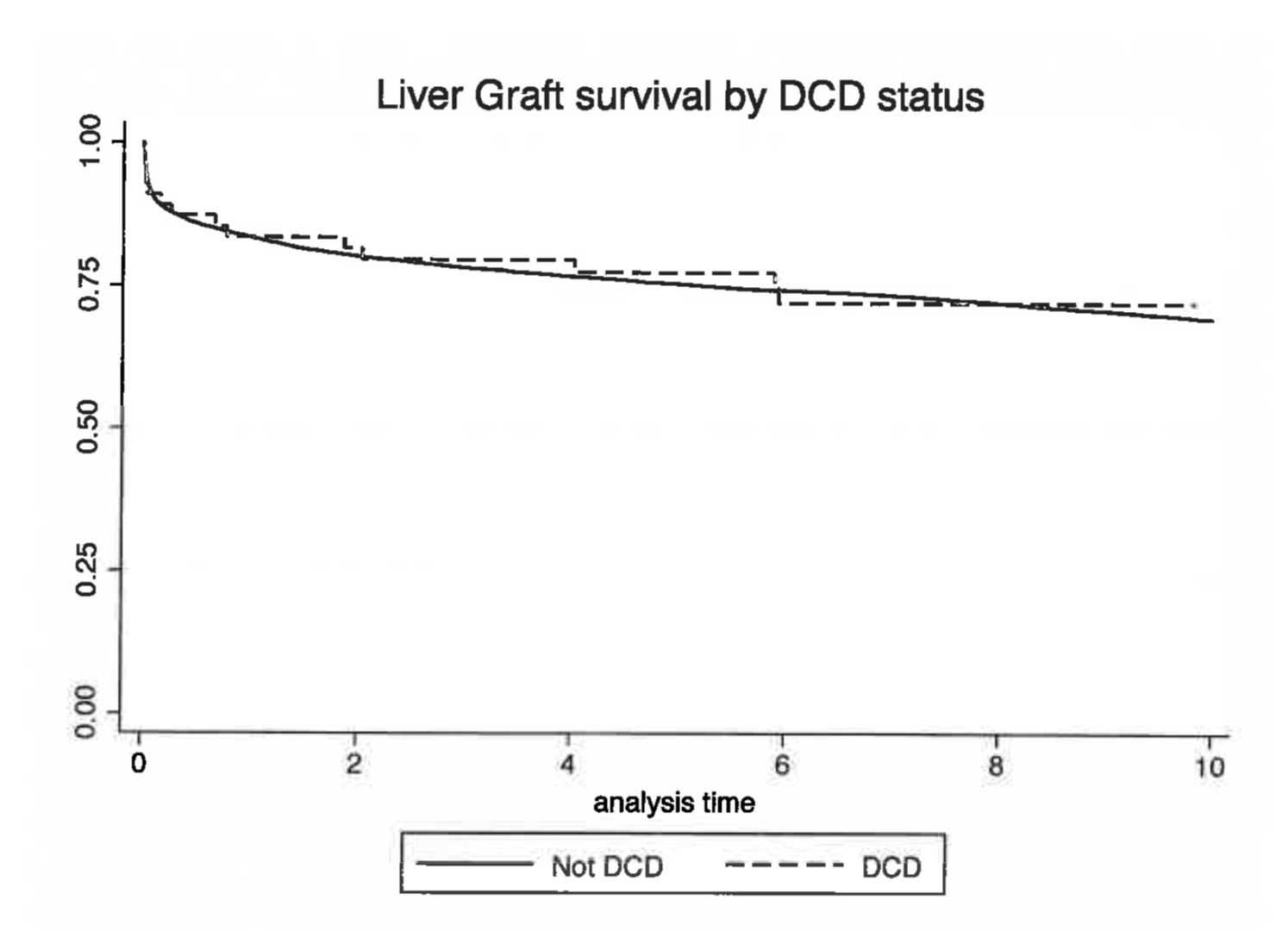

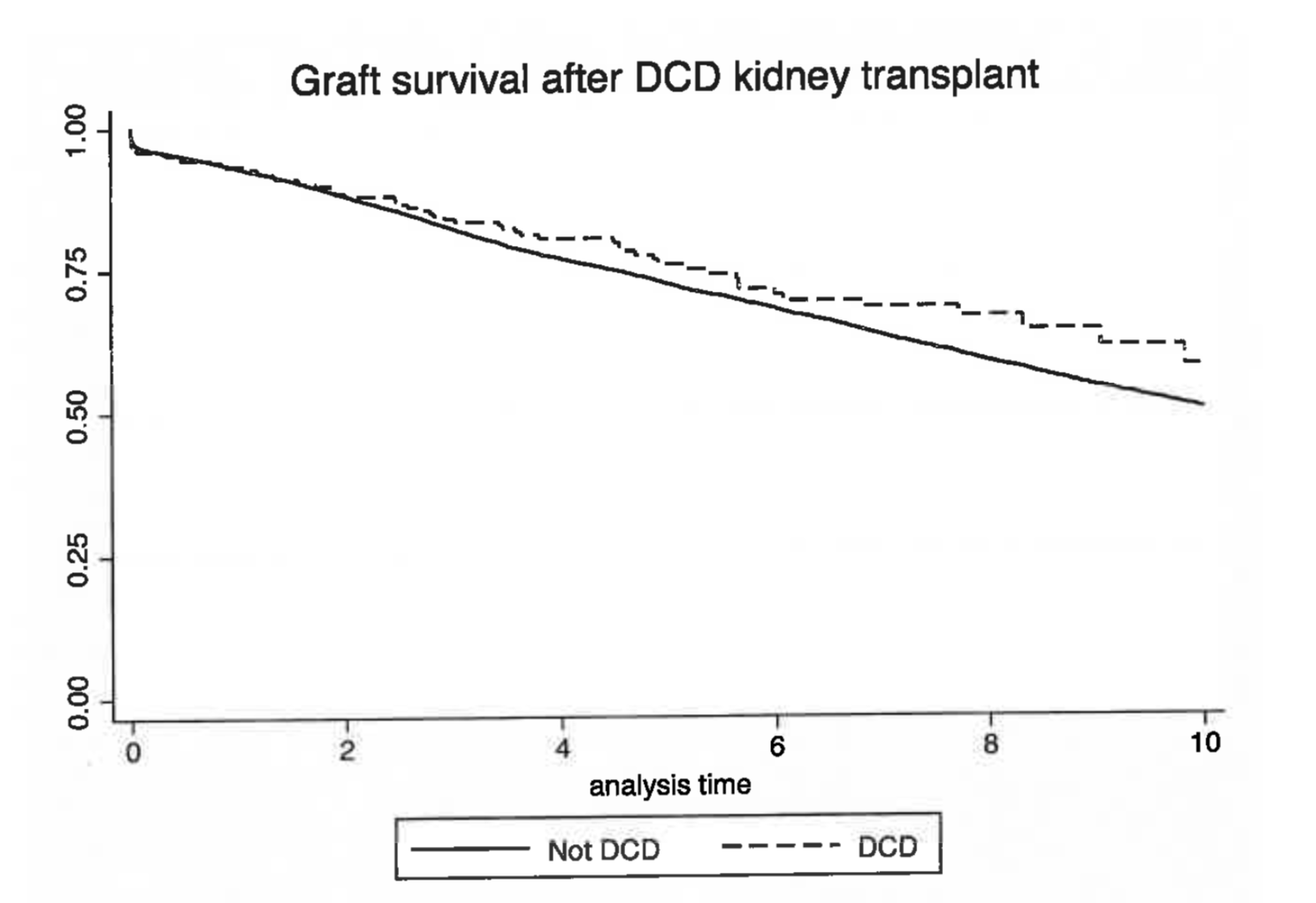

Introduction: Multiple strategies exist to increase the organ pool for pediatric recipients, including using high risk donor organs or donation after cardiac death (DCD) organs. Despite the organ shortage, there still remains a relative reluctance to use livers and kidneys from DCD donors. We examined if this reluctance is warranted by evaluating long term patient and allograft outcomes in pediatric liver and kidney transplant recipients.

Materials and Methods: The United Network for Organ Sharing database was queried to examine outcomes in all liver and kidney transplant recipients from 1996 to 2017. The patients were then divided upon adult and pediatric (under age 18 years) status and donation after brainstem death (DBD) vs. DCD allograft status. Donor and recipient demographic data were examined, and patient and allograft survival were calculated. Categorical differences were compared using the unpaired Student's t-test and nominal variables using either the Chi Square or Fischer's exact test. A p-value of <0.05 was considered to be significant.

Results and Discussion: 55 pediatric patients received a DCD liver. The donors in the two groups were similar in age (11.5 vs. 12.0 years, p=NS, DCD vs. DBD). The average time from withdrawal to aortic flush was 17 minutes in the DCD group. The cold storage times were 7.9 vs. 7.7 hours, p=NS, in the DCD vs. DBD groups. Those who received DCD organs were older in age (7.9 vs. 5.1 years, p<0.05). The average Pediatric End-Stage Liver Disease score was 18 vs. 14, p=NS in the DCD vs. the DBD group. Patients were of comparable illness in both groups when comparing need for life support at the time of transplant in the DCD vs. DBD groups (12.5% vs. 9.7%, p=NS). There was no significant difference in patient or allograft survival between the two groups.

276 pediatric recipients recieved a DCD kidney. The DCD donors had similar ages (21.7 vs. 22.0 years, p=NS), a higher KDPI (27% vs. 23%, p<0.05), longer cold storage time (15.4 vs. 14.9 hours, p=NS), and had a time from withdrawal to aortic flush of 16.6 minutes. Those who received DCD organs were older (12.9 vs 11.0 years, p<0.05), had a shorter length of stay (10.6 vs. 15.2 days, p<0.05), and no significant difference in rejection within the first year (18.1% vs. 21.7%). There were no significant differences in patient or allograft survival between the two groups.

DCD livers and kidneys have similar to if not improved patient and allograft survival, and are an underutilized source of organs in the pediatric population.

Conclusion: When chosen well, DCD organs can be used safely with good outcomes in the pediatric patient population.