Understanding Race and Gender Disparities in Living Donor Kidney Transplant Readiness, Actions, Knowledge, and Socioeconomic Barriers Prior to Transplant Evaluation

Jennifer L Beaumont1, Satoru Kawakita1, John D Peipert1,2, Amy D Waterman1,2.

1Terasaki Research Institute, Los Angeles, CA, United States; 2Division of Nephrology, David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA, Los Angeles, CA, United States

Introduction: Previous research has shown that kidney patients presenting for transplant with higher levels of living donor kidney transplant (LDKT) readiness and knowledge are more likely to ultimately receive LDKTs. For better intervention planning within transplant centers, it is important to determine whether there are race or gender differences in transplant knowledge, readiness, actions towards, or barriers to LDKT prior to or at the start of evaluation.

Materials and Methods: This study estimated differences in LDKT knowledge, readiness, attitudes, and educational preparedness (e.g., number of hours reading brochures about LDKT) using data collected from a sample of 1294 patients, 561 dialysis patients from Missouri and 733 patients from California prior to beginning transplant evaluation. The sample was 43% women, 32% White, 45% Black, and 22% Hispanic. Effect sizes (ES=mean difference / pooled standard deviation) were calculated to provide standardized estimates of group differences.

Results: Patients faced socioeconomic derailers to transplant, assessed by the Kidney Transplant Derailers Index (KTDI; range 0-100, higher scores indicate higher derailers). Black patients had a higher mean KTDI score than Hispanic (ES=0.75) or White (ES=0.74) patients, and women had a slightly higher mean KTDI score than men (ES=0.17). Also, more women reported financial instability (able to survive <1 month on current income) than men (32% vs. 24%, p=0.02).

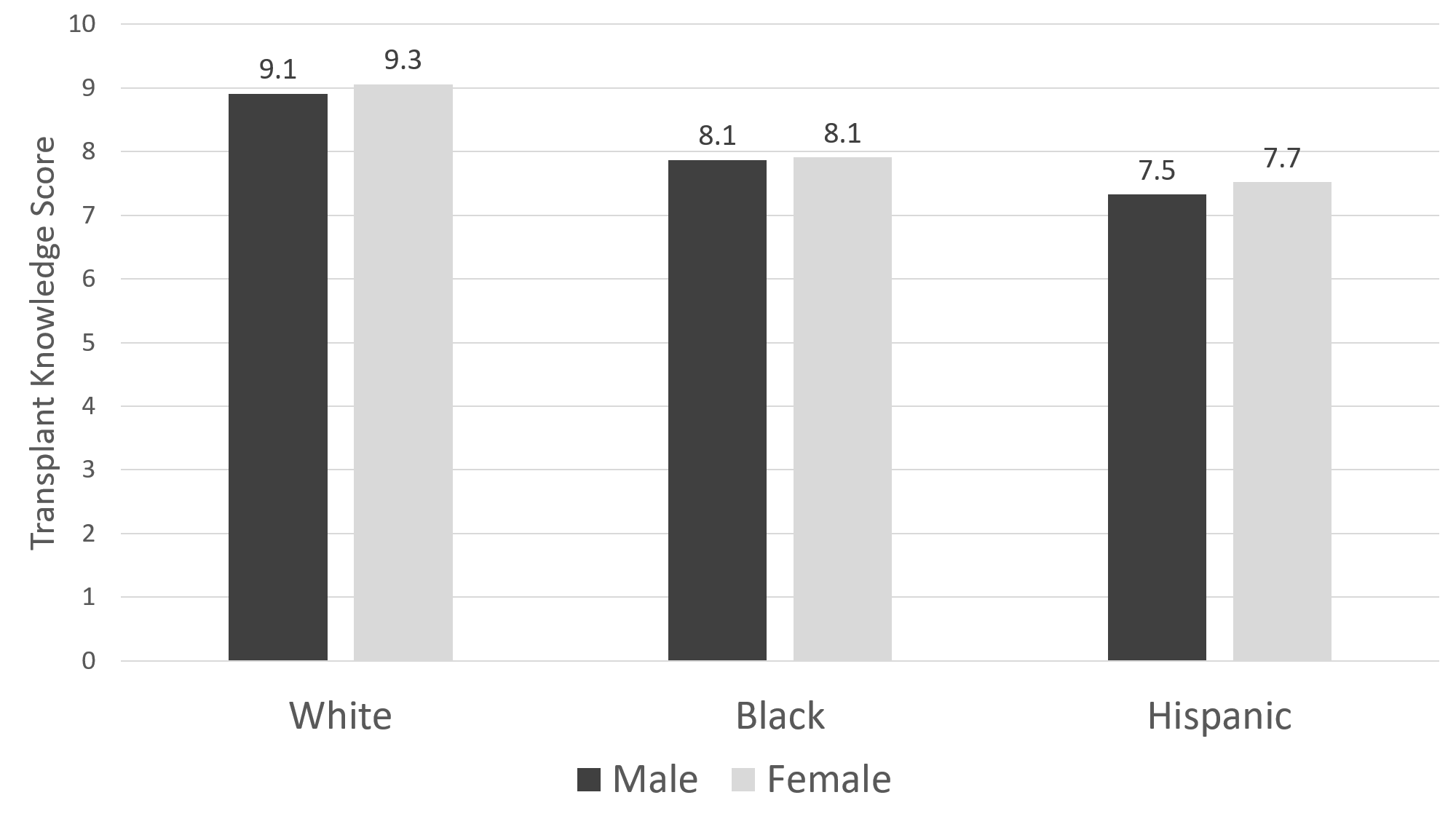

White patients had greater transplant knowledge compared with Black (ES=0.38) and Hispanic (0.52) patients and greater educational preparation (ES=0.23 and 0.42, respectively). There were no gender differences in transplant knowledge (Figure 1).

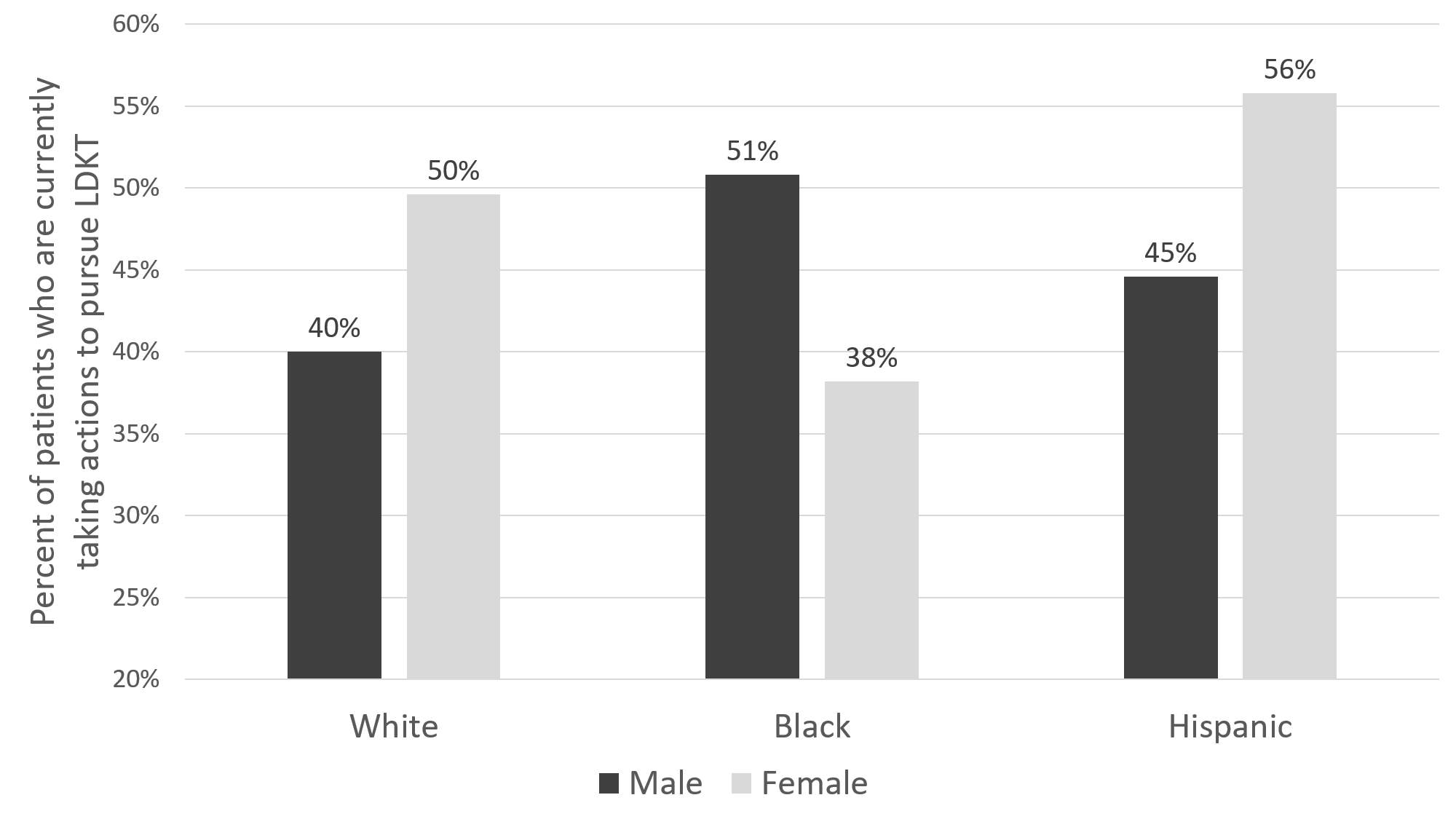

Women had slightly higher readiness to pursue LDKT (49% vs. 45%), but an interaction between race and gender was present (Figure 2). Specifically, the proportion of White and Hispanic women taking actions to pursue LDKT was at least 10% higher than their male counterparts, though this trend was reversed for Black patients.

In comparison to men,women were more likely to have shared LDKT education with people in their lives (33% vs. 24%, p=0.002) and generally talk to people they trust about LDKT (42% vs. 34%, p=0.07). Compared to Black and Hispanic patients, a higher proportion of White patients had read/watched videos about LDKT, shared education about LDKT, generally talked to people about LDKT, and made lists of potential living donors (all p<0.001).

Conclusions: Prior to transplant evaluation, while women face more financial instability, they are also more prepared and more likely to be learning and taking LDKT actions than men. Black and Hispanic patients are generally less prepared for LDKT than White patients before or beginning transplant evaluation. Tailored educational or socioeconomic interventions to increase LDKT considering the different levels of preparedness for LDKT that may exist between racial groups and genders may increase their effectiveness.